By Scott London

Bill Mollison calls himself a field biologist and itinerant teacher. But it would be more accurate to describe him as an instigator. When he published Permaculture One in 1978, he launched an international land-use movement many regard as subversive, even revolutionary.

Permaculture — from permanent and agriculture — is an integrated design philosophy that encompasses gardening, architecture, horticulture, ecology, even money management and community design. The basic approach is to create sustainable systems that provide for their own needs and recycle their waste.

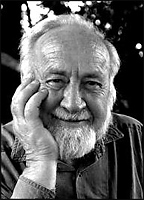

Bill Mollison

Mollison developed permaculture after spending decades in the rainforests and deserts of Australia studying ecosystems. He observed that plants naturally group themselves in mutually beneficial communities. He used this idea to develop a different approach to agriculture and community design, one that seeks to place the right elements together so they sustain and support each other.

Today his ideas have spread and taken root in almost every country on the globe. Permaculture is now being practiced in the rainforests of South America, in the Kalahari desert, in the arctic north of Scandinavia, and in communities all over North America. In New Mexico, for example, farmers have used permaculture to transform hard-packed dirt lots into lush gardens and tree orchards without using any heavy machinery. In Davis, California, one community uses bath and laundry water to flush toilets and irrigate gardens. In Toronto, a team of architects has created a design for an urban infill house that doesn't tap into city water or sewage infrastructure and that costs only a few hundred dollars a year to operate.

While Mollison is still unknown to most Americans, he is a national icon down under. He has been named Australia’s "Man of the Year" and in 1981 he received the prestigious Right Livelihood Award, also known as the Alternative Nobel Prize, for his work developing and promoting permaculture.

I sat down with him to discuss his innovative design philosophy. We met over the course of two afternoons in Santa Barbara in conjunction with an intensive two-week course he teaches each year in Ojai. A short, round man with a white beard and a big smile, he is one of the most affable and good-natured people I’ve met. An inveterate raconteur, he seems to have a story — or a bad joke — for every occasion. His comments are often rounded out by a hearty and infectious laugh.

![]()

Scott London: A reviewer once described your teachings as "seditious."

Bill Mollison: Yes, it was very perceptive. I teach self-reliance, the world's most subversive practice. I teach people how to grow their own food, which is shockingly subversive. So, yes, it’s seditious. But it’s peaceful sedition.

London: When did you begin teaching permaculture?

Mollison: In the early 1970s, it dawned on me that no one had ever applied design to agriculture. When I realized it, the hairs went up on the back of my neck. It was so strange. We’d had agriculture for 7,000 years, and we’d been losing for 7,000 years — everything was turning into desert. So I wondered, can we build systems that obey ecological principles? We know what they are, we just never apply them. Ecologists never apply good ecology to their gardens. Architects never understand the transmission of heat in buildings. And physicists live in houses with demented energy systems. It’s curious that we never apply what we know to how we actually live.

London: It tells us something about our current environmental problems.

Mollison: It does. I remember the Club of Rome report in 1967 which said that the deterioration of the environment was inevitable due to population growth and overconsumption of resources. After reading that, I thought, "People are so stupid and so destructive — we can do nothing for them." So I withdrew from society. I thought I would leave and just sit on a hill and watch it collapse.

The ethics are simple: care of the earth, care of people, and reinvestment in those ends.

It took me about three weeks before I realized that I had to get back and fight. [Laughs] You know, you have to get out in order to want to get back in.

London: Is that when the idea of permaculture was born?

Mollison: It actually goes back to 1959. I was in the Tasmanian rain forest studying the interaction between browsing marsupials and forest regeneration. We weren’t having a lot of success regenerating forests with a big marsupial population. So I created a simple system with 23 woody plant species, of which only four were dominant, and only two real browsing marsupials. It was a very flexible system based on the interactions of components, not types of species. It occurred to me one evening that we could build systems that worked better than that one.

That was a remarkable revelation. Ever so often in your life — perhaps once a decade — you have a revelation. If you are an aborigine, that defines your age. You only have a revelation once every age, no matter what your chronological age. If you’re lucky, you have three good revelations in a lifetime.

Because I was an educator, I realized that if I didn’t teach it, it wouldn’t go anywhere. So I started to develop design instructions based on passive knowledge and I wrote a book about it called Permaculture One. To my horror, everybody was interested in it. [Laughs] I got thousands of letters saying, "You’ve articulated something that I’ve had in my mind for years," and "You’ve put something into my hands which I can use."

...MORE HERE...

No comments:

Post a Comment